Eventually, each architect is presented The Fountainhead. Often, that is finished with good intentions: somebody reads Ayn Rand’s 1943 novel about an idealistic architect at struggle with a cynical society and is reminded of the architect in their very own lives, their good friend or nephew or whomever. They purchase the architect a replica, pondering they are going to recognize seeing their career represented in literature.

Generally although, Fountainhead pushers have one other agenda. Rand’s 753 web page doorstop was not only a work of imaginative literature; it was a automobile for Ayn Rand to push her political ideology, an excessive type of capitalist individualism known as Objectivism. Rand hoped readers of The Fountainhead can be satisfied of the evils of collectivism, particularly any form of socialism, which in her view suppresses the entrepreneurial spirit of geniuses like her architect hero Howard Roark. She wished to alter the way in which folks voted, not simply how they considered structure.

As it’s a work of political propaganda, The Fountainhead falls wanting John Keats’s normal for genuine literature. In an 1817 letter to his brothers George and Thomas, the poet coined the time period “adverse functionality” to explain the power of nice authors to place their very own opinions to the aspect after they got down to write. The function of the creator, in Keats’s view, is to not push an agenda however to provide life to no matter concepts emerge organically inside the imaginative house of the poem or novel.

A lofty normal? Perhaps. However the novels listed right here come nearer to the mark than The Fountainhead. They run the place Rand’s guide solely walks — that’s, they provide genuine literary expression to architectural concepts.

Daniel Burnham’s “White Metropolis,” constructed in 1893 for the Chicago World’s Truthful. Unidentified Photographer, Public Area by way of Wikimedia Commons.

The reader would possibly right here exclaim that I’m dishonest. “The Satan within the White Metropolis isn’t a novel in any respect,” they’ll say, “it’s a work of non-fiction!”

True as which may be, The Satan within the White Metropolis is by Keats’s normal a transparent instance of imaginative literature. In re-telling the occasions surrounding the 1893 Chicago World’s Truthful and its architect, Daniel Burnham, creator Erik Larson set out, above all else, to inform a narrative and to take action as powerfully as he might. As New York Occasions critic Janet Maslin gushed, Larson “relentlessly fuses historical past and leisure to provide this nonfiction guide the dramatic impact of a novel, full with plentiful cross-cutting and foreshadowing.”

Larson’s strategy is nicely suited to his dramatic subject material. The story alternates between two narratives: the planning and improvement of the World’s Truthful below architect Daniel Burnham, who used the honest as a chance to showcase the grandeur of the Beaux Arts Fashion, and the exploits of serial killer H.H. Holmes, who used the honest as a chance to prey on naive out-of-towners.

In a grim ironic twist, Holmes was one thing of an architect himself, remodeling a Chicago rooming home right into a “Homicide Citadel” full with trapdoors, greased chutes and soundproof rooms. Certainly, the parallels between Burnham and Holmes are the thematic coronary heart of the guide, lending this true story literary gravitas.

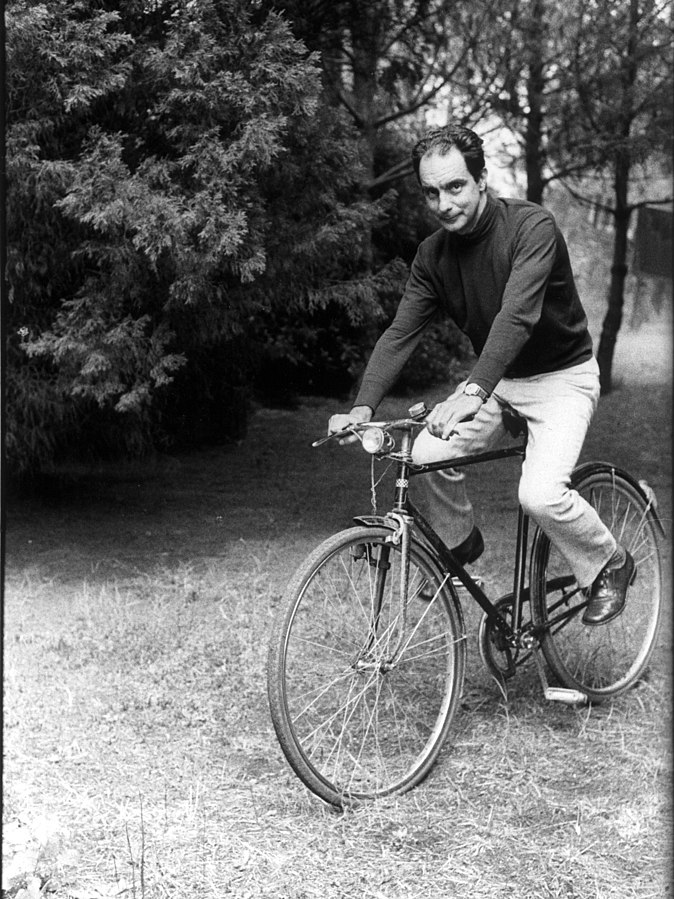

Italo Calvino driving a motorcycle in 1970. Unknown Photographer, Public Area by way of Wikimedia Commons.

Like an amazing constructing, Invisible Cities is a guide that was designed to be inhabited slightly than merely skilled as soon as. The allegorical novel is structured as a collection of conversations between Marco Polo, the thirteenth century Italian explorer, and Kublai Khan, the Mongol emperor of China.

Polo and Khan did meet in historical past, however this guide isn’t drawn from any historic sources. The conversations are merely a framing machine, permitting Polo to explain 55 fictitious cities to the emperor, locations he claims to have visited. Every metropolis is a parable for a special side of human nature, and because the novel progresses, it turns into clear that the topic Polo has discovered essentially the most about in his travels is himself. Locations, it appears, are illuminated by the preconceptions we carry to them.

Whereas the story has a free-floating and dreamlike construction, there’s a plot twist that happens midway via the novel. Pressed by Kubla Khan to explain his residence metropolis of Venice, Polo explains that he has been doing that each one alongside. Fedora, Zoe, Zenobia, and all the opposite fictional cities he recounts are all simply Venice seen from totally different vantage factors.

Home of Leaves by Mark Z. Danielewski (2000)

Leaves are rather more intricate than they seem like at first. Photograph by Jon Sullivan, 2003, Public Area by way of Wikimedia Commons.

Home of Leaves is type of just like the studying equal of being trapped inside H.H. Holmes labyrinthine Homicide Citadel. The textual content is specified by a trend that’s something however linear, with copious footnotes resulting in their very own footnotes which themselves have footnotes, all making copious references to books and movies which can be typically actual, typically not. At occasions, the textual content is organized unusually on the web page and the guide should be rotated to be learn. At different occasions, a number of narrators interrupt each other in a disorienting trend. Even the style is difficult to find out. Whereas most readers contemplate Home of Leaves a horror story, the creator himself has described it — bafflingly maybe — as a love story.

However Home of Leaves gives the reader rather more than mere confusion. By traversing this experimental guide, the reader is ready to share within the protagonists’ disorientation, providing a novel, typically claustrophobic expertise of imaginative identification. The guide follows a household whose home comprises an infinite collection of hidden rooms — an allegory, maybe, for the psyche, household dynamics, educational criticism, historical past and extra. (Maybe the checklist can be infinite). For architects, the mysteries of this novel are a potent reminder that readability, rationality, and openness aren’t all the time preferable. Generally persons are drawn to the darkness.

Am Gestade, one in all many Viennese streets Austerlitz traverses as he searches for his hidden previous. Photograph by Jorge Franganillo, CC BY 2.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0>, by way of Wikimedia Commons

Can a murals communicate to each the center and head on the identical time? Or do the mind and the feelings reply to totally different sorts of inventive expertise, one craving crucial distance and the opposite empathic closeness? These aren’t simply questions that Austerlitz poses to the reader, they’re the questions confronted by the novel’s eponymous protagonist.

Jacques Austerlitz is an architectural historian who lives a solitary, itinerant life. He’s fascinated with the way in which buildings and avenue layouts can reveal the buried histories of locations, forsaking an goal file of how folks lived — abnormal folks, that’s, not simply the kind of folks whose names find yourself in historical past books. Sooner or later, Austerlitz stumbles throughout a startling truth about himself. He learns that the couple who raised him in England weren’t his organic mother and father. His precise mother and father have been a Jewish couple from Vienna who perished within the Holocaust. That they had despatched their younger son, then aged three, to security in England utilizing an underground program generally known as the kindertransport.

Austerlitz applies his abilities as an architectural historian to analysis the buried historical past of his personal mother and father, who appear to have left few traces behind. He’s then confronted with the chance that he had unknowingly been on the lookout for all of them alongside. Might his curiosity in architectural historical past have been, unconsciously, a manner of attempting to uncover his personal roots? This query, which might intrigue Calvino’s Marco Polo, is simply one of many many tantalizing mysteries of this masterful novel about reminiscence and loss.

Cowl Picture: Freepik, Attribution by way of Wikimedia Commons